You Are

Here !

Articles of Interest |

Free

Speech ??

Use It - Or Lose It !!

|

|

|

|

|

An

article from the Spectator, November 2001

What Enoch was really saying

Simon Heffer says that angry demonstrations by British

Muslims against the war on terror suggest that the

‘Rivers of Blood’ speech should have been

heeded:

Simon Heffer is a columnist for

the Daily Mail.

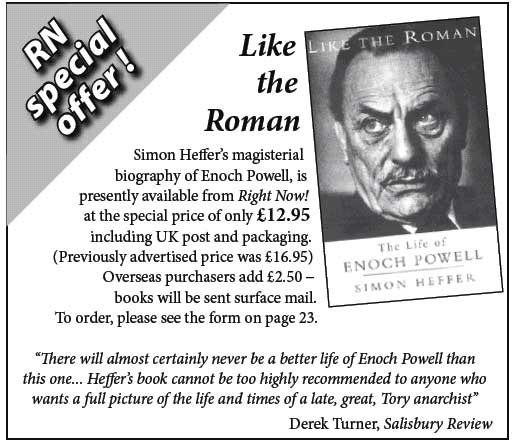

His life of Enoch Powell, Like

the Roman, is published by Weidenfeld and Nicolson/Phoenix

Paperbacks.

|

|

Powell's chief concern was culture,

not race.

Reading reports of a church in Bradford being set fire to

by Islamic extremists a fortnight ago, and wondering only

half in jest whether these people should be asked to sign

a pledge of toleration towards Christians, my thoughts turned

again to Enoch Powell. The recent exposure of cracks in our

so-called ‘multicultural’ society, as a result

of the war against terrorism, has brought his Birmingham speech

of April 1968 back to several people’s minds. Lord Deedes

has claimed that Powell’s remarks — known to posterity,

somewhat inaccurately, as the ‘Rivers of Blood’

speech — were to blame for our current problems with

multiculturalism. The line is that Powell created a climate

in which it became impossible for politicians to address matters

of immigration policy in a fashion that would have avoided

today’s difficulties. The notion is, it seems, that

integration and a better establishment of a brotherhood of

man would have been far easier but for Enoch stirring things

up. It was an argument taken up, too, by the editor of this

magazine; and yet for all the eminence of those who advance

it, it is nonsense.

Anyone who has studied immigration policy in the 1950s and

1960s — and Lord Deedes was a Cabinet minister for part

of that time — knows that sensible and rational treatment

of the issue was off the agenda long before Powell raised

the subject. Powell himself, as a housing minister in 1956,

sat on a cross-departmental committee that considered aspects

of the effects of mass immigration. Even then he was aware

of problems growing in his own Wolverhampton constituency

because of the concentration of immigrants in small urban

areas. The decision by the committee to ignore his representations

on the subject was not unusual. As Andrew Roberts has pointed

out in his excellent analysis of Tory policy on immigration

in the 1950s, the options ranged from turning a blind eye

at one extreme to sheer cowardice at the other. Often, these

issues are seen in the narrow context of controlling the sheer

numbers of immigrants. Powell, however, saw early on that

the cultural clash which such large numbers caused was by

far the more explosive problem, and required even more urgent

treatment.

It was not so much the colour of people’s skins that

Powell was alerting us to in his speech; it was the problem

of allowing their cultures to supplant the indigenous one.

The word ‘multiculturalism’ was not in his vocabulary,

but the speech was a warning against it. It was a warning

to politicians of the mess they were storing up for the future

by their refusal to act on this problem when it was ‘a

cloud no bigger than a man’s hand’. The angry

demonstrations by British Muslims against the native civilisation

that we have seen in recent weeks, and which have helped drive

the Home Secretary to propose some draconian laws to keep

the peace in multicultural Britain, are symbols of the extreme

behaviour that has been made inevitable by the failure to

heed what Powell said.

In 1958, after the Notting Hill riots, the Tory backbencher

Cyril Osborne — a veteran of the Great War and no weakling

— was reduced to tears by the humiliation he received

at the hands of his colleagues at a meeting of the 1922 committee,

when he urged action on the government. Powell was present

at the meeting, and told me 35 years later that his remaining

silent during the attack on Osborne by bien-pensant Tory MPs

was something he had felt ashamed of ever after. Very few

of them had any experience of sitting for areas where large-scale

immigration was a problem; indeed, Osborne himself sat for

rural Lincolnshire. Only with great reluctance, and to little

discernible effect, did the Macmillan government push through

the 1962 Commonwealth Immigration Act, to try to control numbers.

It failed utterly to have any effect on the main social problem

caused by immigration: that people sometimes of a culture

at great variance to that of their host country settled in

communities and adopted a communal outlook, rather than settling

across the whole country in a way that would allow them to

integrate most successfully into the predominant culture.

No one took any steps to deal with this problem before 20

April 1968, so to argue that Powell’s speech made any

odds in the matter is entirely spurious. Indeed, had any attempts

been made to discourage the growth of what has come to be

known as multiculturalism, Powell would probably never have

felt the need to speak as he did.

In fact, recent events such as the burning of that church,

and the open allegiance that some British subjects of Muslim

origin feel towards the enemies of their country, cast Powell’s

speech in a wholly different light. It can, and should, be

seen as the first blast of the trumpet against the dangers

of multiculturalism, but what Powell called communalism. The

generation of politicians of all parties who failed to deal

with this problem is now mostly dead. It will not do for the

few who survive, or for their successors, to attack Powell

for the crime of being right, and for speaking up after over

ten years of watching the political class of which he was

a member doing less than nothing about a problem that was

even then already painfully apparent to millions from all

ethnic backgrounds.

|

|

|

Powell well

knew the extent of the cowardice he was up against.

The supreme function of statesmanship,’ he began when

he rose to speak on that Saturday morning nearly 34 years

ago, ‘is to provide against preventable evils.’

He identified the main impediment to the required act of

statesmanship, one apparently still in place today: ‘If

only people wouldn’t talk about it, it probably wouldn’t

happen.’ He defended himself for breaking the taboo.

‘Those who knowingly shirk [the responsibility to

discuss problems connected with immigration] deserve, and

not infrequently receive, the curses of those who come after.’

Repeating the first of two incendiary anecdotes, about the

constituent who told him that within 15 or 20 years ‘the

black man will have the whip hand over the white man’

(the other was the one about the little old lady who had

shit put through her letter-box), Powell predicted what

would happen to him. ‘I can already hear the chorus

of execration. How dare I say such a horrible thing? How

dare I stir up trouble and inflame feelings by repeating

such a conversation? The answer is that I do not have the

right not to do so.’ With parts of Britain, including

his own constituency, undergoing a cultural transformation

‘to which there is no parallel in a thousand years

of English history’, Powell asserted that, as an MP

confronted with such concerns, ‘I simply do not have

the right to shrug my shoulders and think about something

else.’ His party, however, happily did, then and for

many years afterwards, which perhaps explains the sensitivities

of some of its luminaries on the subject even today.

Much of the speech, as is well known, was about instituting

a system of voluntary repatriation. For all the revulsion

this caused at the time, that particular idea was Tory party

policy and was enshrined in law in 1971. Yet this plea was

given force by Powell’s warnings of what would happen

if multiculturalism were to grow unchecked. He wanted everyone

to be equal before the law. ‘This does not mean,’

he argued, ‘that the immigrant and his descendants

should be elevated into a privileged or special class.’

Those who have wondered why the inflammatory statements

of certain Muslim extremists in this country, including

calls for the murder of the President of Pakistan, have

not caused those extremists to be prosecuted would do well

to think about Powell’s warning.

Until a few years before he made the speech, Powell had

thought it would be possible to integrate the immigrant

population into the indigenous society. Now the sheer numbers

and their concentration on certain areas made such a hope

impossible. Now he gave his starkest warning about what

we call multiculturalism: ‘There are among the Commonwealth

immigrants who have come to live here in the last 15 years

or so many thousands whose wish and purpose is to be integrated

and whose every thought and endeavour is bent in that direction.

But to imagine that such a thing enters the heads of a great

and growing majority of immigrants and their descendants

is a ludicrous misconception, and a dangerous one to boot.’

Powell knew that economic circumstances, such as the availability

of cheap rented accommodation, had hitherto acted to force

immigrants to settle in small areas. ‘Now,’

however, he warned, ‘we are seeing the growth of positive

forces acting against integration, of vested interests in

the preservation and sharpening of racial and religious

differences, with a view to the exercise of actual domination,

first over fellow-immigrants and then over the rest of the

population.’ It was then ‘a cloud no bigger

than a man’s hand’; but he quoted a Labour minister,

and fellow West Midlands MP, John Stonehouse, who had warned

of the dangers of Sikhs campaigning to maintain customs

‘inappropriate to Britain’. Stonehouse had said

that ‘to claim special communal rights ...leads to

a dangerous fragmentation within society. This communalism

is a canker; whether practised by one colour or another,

it is to be strongly condemned.’ Yet nobody listened,

either to Powell or to Stonehouse.

Everybody knows the peroration of the speech, or thinks

he does. What immediately preceded it, however, was the

definition of the evils of multiculturalism when allowed

to flourish in a monocultural society unwilling and unprepared

for it. It is worth quoting in full:

Here is the means of showing that the immigrant communities

can organise to consolidate their members to agitate and

campaign against their fellow-citizens, and to overawe and

dominate the rest with the legal weapons which the ignorant

and ill-informed have provided. As I look ahead, I am filled

with foreboding. Like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the

River Tiber foaming with much blood’.

He concluded that ‘to see, and not to speak, would

be the great betrayal’. The hatred poured down on

him was as much in resentment of his drawing attention to

this destructive force as in an ignorant belief —

for the text does not bear such an assumption out —

that Powell was being ‘racist’.

I have often wondered, since 11 September, what Powell would

have made of current events. He would not, I suspect, have

approved of our support for America, because he regarded

America in terms not very far removed from the Guardian’s

or Osama bin Laden’s, though in the second of those

cases for very different reasons. Yet he would have been

more diverted by the spectacle of those who owe allegiance

to the Crown declaring, instead, that they would rather

fight for the Taleban. He would have reacted with dismay,

but not surprise, at stories of mosques being hijacked from

their congregations of decent, moderate Muslims and manipulated

into breeding grounds of extremism. He would have watched

the reporting of the church being burned and seen it as

utterly symbolic of what happens when you encourage an alien

culture not to co-exist with, but to confront, another.

He would have been in no doubt that he had been proved right.

His speech did not prevent remedial action being taken to

prevent the growth of multiculturalism. There was never

any will to do it. Because of the damage done even by the

accusation of racism, no politician would have attempted

to prevent it, even if Powell had not spoken. Even in the

last election campaign Mr Hague, then the Tory leader, made

some half-witted comments in support of multiculturalism,

a phenomenon he plainly did not understand. And, when Lady

Thatcher quite sensibly denounced the whole concept as divisive,

Michael Portillo tried to have her bundled into a cupboard

and not let out again. We have taken a long time to learn,

but, had we only had eyes to see and ears to hear, Enoch

tried to teach us. Rather than make him into the most inappropriate

scapegoat for the failings of his whole political generation,

and others since, we should instead offer him the most contrite

of posthumous apologies.

2001

The Spectator.co.uk

|

|

|

"This is, in theory still

a free country, but our politically correct, censorious

times are such that many of us tremble to give vent

to perfectly acceptable views for fear of condemnation.

Freedom of speech is thereby imperilled, big questions

go undebated, and great lies become accepted, unequivocally

as great truths."-

Simon Heffer, Daily Mail, June 7th 2000.

www.dailymail.co.uk

|

http://www.right-now.org

|

|

|

|